All Saints Brockhampton.

The Architect’s Error

As it says for all to see in the church porch, architect W.R. Lethaby’s error at All Saints’, Brockhampton, was that “The experimental nature of the building led to some disasters – part of the west wall collapsed.” As a result, Lethaby never built again.

In a letter to his sister, the architect confessed that “The responsibility of building always withers me up, and now that the cost has mounted up terribly in a scheme of my own to build without contractor, it is quite terrible to wake up to a doubt of the foundations.” After the failure at Brockhampton, Lethaby limited himself to teaching and writing.

Nave of All Saints Brockhampton, Herefordshire.

Lethaby’s error at All Saints’ Church was in trying to build in accordance with William Morris’ “never-never-land of pseudo-medieval guild socialism” [1]. Despite preparing over two hundred drawings for the project, and living on-site so that he could work closely with the trades and allied crafts workers involved in the construction process, Lethaby could not narrow the gap between ‘design’ and ‘doing’, and mistakes were made. According to the online history of the church [2], as the project “neared completion a structural crack appeared in the east wall of the south transept due to an inadequate foundation.”

Although Lethaby paid for his error – in many ways, including literally by paying for the necessary remedial work out of his own pocket – some 80 years later, Viscount Esher, then Rector of the Royal College of Art, described Lethaby as “the heaven-sent antidote to [William] Morris.” For Esher, Lethaby was “able to speak of a new architecture more attractively, and more in the language of a later generation, than any other Englishman…”

Windows and Light Fittings, South Side, All Saints Brockhampton.

One of Two Tapestries designed by Edward Burne-Jones and made in The Morris Workshops.

Well-Making

While working on his church at Brockhampton, Lethaby gave a famous lecture at the Birmingham Municipal School of Art on William Morris’ understanding of Art as being “the spirit of man put into the body of his labour; the intrinsically right principle in the making of things – Work religion.” In this, Lethaby was clearly restating the Arts & Crafts definition of the word ‘Art’ as meaning “the elements of good quality, reasoned fitness, and pleasantness in all work done by hand for necessary service.”

Lethaby subsequently rephrased this in summary terms as “art may be thought of as THE WELL-DOING OF WHAT NEEDS DOING”, and this slogan both informed and guided Raymond Unwin’s highly influential ‘Town Planning in Practice’ of 1909. As Unwin commented, “We have in a certain niggardly way done what needed doing, but much that we have done has lacked the insight of imagination and the generosity of treatment which would have constituted the work well done; and it is from this well-doing that beauty springs.”

By 1940, aspiring places like Coventry were designing the modern city under the same slogan: ‘THE WELL MAKING OF THAT WHICH NEEDS MAKING’.

Decorative and Functional Details from All Saints Brockhampton.

In old age, Lethaby declared [3] that “We have to refound art on community service as the well-doing of what needs doing”, and his own life became very much about the idea of art as service. According to Viscount Esher, “Lethaby once set out in epigrammatic form a simple syllabus of his accumulated experience. ‘Life is best thought of as service; service is common productive work; labour may be turned into joy by thinking of it as art, art, thought of as fine and sound ordinary work, is the widest and best form of culture; culture is a tempered human spirit’.” [4]

An early image of the church at Brockhampton.

North Elevation, showing “knotwork” windows.

Also in 1901…

During what became an increasingly busy year for Lethaby, in 1901 he also became Professor of Design at the Royal College of Art, and the following year the sole Principal at the London County Council Central School of Arts and Crafts. Initially founded by Lethaby in 1896, ‘The Central’ was a logical consequence of the Art Workers Guild he had co-founded in 1884 with other young architects associated with R.N. Shaw’s office. But it was in Germany, through the later Deutscher Werkbund movement and Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus, that Lethaby’s unique contribution to 20th century finally found its fullest expression. As Lethaby said, “German advances have been founded on the English Arts and Crafts.” [5]

Lethaby also shaped our contemporary understanding of the importance of conservation and preservation. In 1906, he was appointed Surveyor of Westminster Abbey, and his work for the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (founded by William Morris and others in 1877) is still recognised today through its awarding of the annual Lethaby Scholarships for architectural conservation.

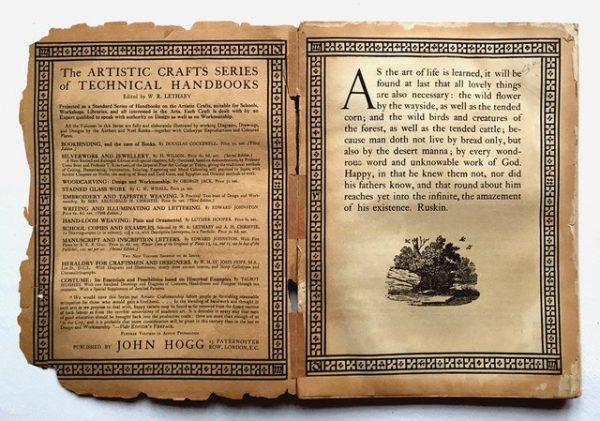

In 1901, Lethaby also began to commission and edit the popular ‘The Artistic Crafts Series of Technical Handbooks’. These important texts, written by leading practitioners of the time, covered a diverse range of subjects, and included: ‘Book-Binding and the Care of Books’ (Douglas Cockerell), ‘Silverwork and Jewellery’ (H. Wilson), ‘Woodcarving: Design and Workmanship’ (George Jack), ‘Stained Glass Work’ (Christopher Whall, who did the windows at All Saints), ‘Embroidery and Tapestry Weaving’ (Mrs. Archibald H. Christie), ‘Heraldry for Craftsmen and Designers’ (W.H. St. John), ‘Woodblock Printing’ (F.Morely Fletcher), ‘Dress Design’ (Lethaby, himself), and so on.

In his Editor’s Preface to Edward Johnston’s ‘Writing, Illuminating & Lettering’ (1906), Lethaby states that “…true design is an inseparable element of good quality, involving as it does the selection of good and suitable material, contrivance for special purpose, expert workmanship, proper finish, and so on.”

One of Lethaby’s stated intentions behind the ‘Artistic Crafts Series’ was to “put artistic craftsmanship before people as furnishing reasonable occupations for those who would gain a livelihood.” Indeed, when he published his own ‘Architecture – an Introduction to the History and Theory of the Art of Building’ in 1911, Lethaby was ‘reproached for having given away the secrets of architecture for a shilling.”

Of course, such things as ‘true design’ and the benefits of ‘well-making’ can be simply dismissed today as irrelevant to our current building of a very different kind of world. Even so, and despite our sense of urgency and the limited resources now at our disposal, when visiting Lethaby’s church at Brockhampton we might do well to recall this old architect’s advice to others:

“In church, cathedral, cloister, hall

Some hours each day I’d spend-

And this a touch of dignity

To all your work will lend.”

A footnote…

They say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but it is difficult to imagine what Lethaby would have made of what Norman from New Zealand found on the 22nd floor of the Hotel Monterey Grasmere, in Osaka, Japan. “The faux chapel in the lobby” is a scaled down replica of Lethaby’s church at Brockhampton, and has become a popular wedding venue. What would have alarmed Lethaby most? The hotel’s description of what Norman discovered, or the risk-analysis of building foundations in Osaka Prefecture?

“This authentic looking chapel is surrounded by green grass and vivid flowers and illuminated from above by the extensive glass roof. The design imitates the churches of the Cotswolds, described by the renowned designer William Morris as the most beautiful in England. Our chapel recreated the beauty of the Cotswolds, from its rolling green hills to its traditional arts and crafts culture.” [6]

Sources:

- Viscount Esher: ‘A Broken Wave: the rebuilding of England 1940-1980, 1981.

- http://www.allsaintsbrockhampton.org/history/, accessed 28.05.2019.

- W.R. Lethaby: ‘The Town Itself / A Garden City is a Town’, 1921.

- Viscount Esher: Forward to ‘SCRIP’S AND SCRAPS by W.R. Lethaby gathered and introduced by Alfred H. Powell’, 1956.

- W.R. Lethaby: ‘Form in Civilization’, 1922.

- https://www.hotelmonterey.co.jp/en/grasmere_osaka/facilities/ accessed 13.08.2019.

David Patten | Biography

After studying Fine Art in Birmingham, and Painting under Peter de Francia at the Royal College of Art in London, David Patten’s work has emphasised the importance of cultural democracy and collaboration. He has contributed to many award winning projects, including the re-use scheme at Electric Wharf in Coventry (Bryant Priest Newman Architects) and the restoration of Stourport Canal Basins (British Waterways). His current work on W.R.Lethaby’s impact on post-War rebuilding is a direct result of his almost obsessive interest in the ‘Monumental Studio’ of the little known sculptor and ecclesiastical decorator William Forsyth, who was working in Worcester during the latter half of the 19th century. David Patten is also a Patron of The Baskerville Society..

Thank you for this informative post. I have added this to the Facebook Page for All Saints’, and placed a link below, which I hope is acceptable.

Mark Giles – social media assistant on Facebook for All Saints’ Brockhampton, Herefordshire.

Thanks Mark. Here’s your link: https://www.facebook.com/allsaintsbrockhampton