The beautiful little church of St Mary and St David at Kilpeck is one of the glories of Herefordshire.

Head west from Ledbury towards Wales, between the Dye and Dore valleys, to the tiny hamlet of Kilpeck (pop 211) and there you will find an architectural gem; a church built around 1140 decorated with masterpieces of red sandstone carvings and sculptures of such diverging themes and styles that no one interpretation of them seems to exists.

Described as one of the ‘most perfect Norman Churches in England’* the Parish Church of St Mary and St David at Kilpeck has stonework that has survived, relatively unscathed, the vagaries of war, famine, plague and religious fervour. These carvings are recognised as the best examples of the Herefordshire School of Romanesque Sculpture.

The church is open every day from nine until dusk. I have visited twice, once on a bitterly cold winter day and yesterday, in the heatwave heat of early June. On both occasions I have had the place to myself. This isolation and quietude add much to the experience of a visit there. There is the feeling you have stepped out of the twenty-first century and back into history.

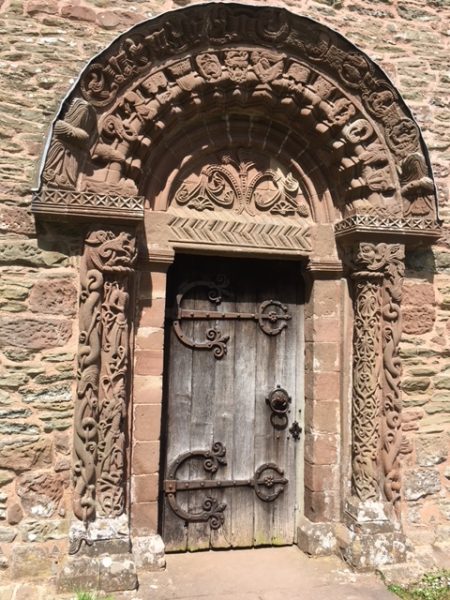

Look closely at the carvings that abound at Kilpeck, both within and without. Here is the magnificent entrance of the South Door with its Tree of Life tympanum; it’s column stems where strangely dressed figures dubbed the ‘Welsh Warriors’ are clothed in soft shoes and Phrygian caps such as French revolutionaries might wear.

Look up at the corbel table and its gallery of over eighty ‘grotesques’ that runs around the whole of the outside of the church. Styles change with almost no repeating patterns or images. It is said that the lack of symmetry is a unique Herefordshire quality. There is a wealth of detail in the carvings and you will wonder what exactly is being represented here and where the carvers’ influences might have come from.

This mystery of interpretation makes the carvings particularly beguiling. The feudal society that built this church was dominated by early Christian culture and perhaps the images were used to educate an illiterate congregation? But that can only be a part explanation. Were the masons influenced from Scandinavia as well as the pilgrimage routes of southern Spain and France? Is it agreed there is a mix of styles from Vikings, Saxons, Celts, Frank and Spaniards?

The Welsh Warriors

Amongst the corbel carvings there are mythical creatures and there are scenes of religious iconography and daily life. Records show there was a weekly fair at Kilpeck: do these dancers, musicians and animals; a ram, dogs, doves, bears, rabbits and an upside down pig represent the nature of village life? With the Green Man and the Sheela-na-Gig are we reaching back into a pagan past that has been absorbed and reinterpreted by early Christianity ? At least two terrifying creatures, the Mantichore and the Basilisk are recognizable from the Medieval Bestiary. Are those two entwined figures, wrestlers or dancers or perhaps lovers or maybe even, as someone has suggested, a gay couple? Are the snakes a symbol of Christian evil or are they pagan symbols of rebirth and the continuation of life?

Snake detail on South Door

Entwined figures

Green Man

Sheela-na-Gig and Monster

Even today we have no certainly of interpretations but the history of interpreting can be entertaining. The rare Sheila-na-Gig, a woman holding her vulva wide open, was apparently described by a straight-laced scholar as ‘A fool opening his heart to the devil’! Perhaps it was this interpretation that saved the explicit carving from destruction. Was it Victorian puritanism that removed some of the other missing corbels? More speculation.

Within the simple whitewashed interior of the church there are more treasures to wonder at. There is a pre-Saxon stone stoup, carved as two hands clasping a pregnant belly that has been given snakes for feet and which today has been filled with June flowers.

Stone Stoup

On the day of my visit, a poster on the village green invites everyone for tea the following Sunday to meet with the new vicar. It seems incredible that there has been continuous worship for over a thousand years at Kilpeck.

On my visit to the church I felt a calmness and spirituality all about, but most of of all I felt a profound connection to the past. The skill of those early Herefordshire craftsmen present in the survival of their artistry transported me beyond the twenty first century and the rural farmlands of the Marches into a collective past that places us firmly within the history of Europe and early Christendom.

* Simon Jenkins England’s Thousand Best Churches